Classifying Thatcher’s hegemony

Stuart Hall’s The Neo-Liberal Revolution [PDF] is an analysis of

the contrasting views and systems which have shared the popularity of the

British public since 1945.

Firstly, the aftermath of the Second World War prompted an

almost-unilateral level of support for the creation of a welfare state. It was

the Labour party of Attlee that first pulled it together; but William Beveridge,

upon whose famous report the welfare system was based, was a Liberal, and the

plans even had support from the Conservative members of the wartime National

Government. While Labour, at the time still a party which could claim to

represent the working people of Britain, had made great gains in working class

and poorer areas, it was not until the war that the wider population began to

take notice of the situation of those in poverty around the country this

happened when children from destitute inner-city areas were evacuated to the

homes of wealthy country families. Although the level of camaraderie and

collective British spirit at the time has been overplayed, this, perhaps, also

had an effect. The desire for a cradle to grave support system was so deep that

the Tory party were unable to win despite their entire campaign being based on

the fact that ‘they’ had won the war with their candidate for PM Churchill.

It was not until 1979 that the idea of the welfare state was

challenged, when Margaret Thatcher led the first of her three successive governments

into an ‘ungovernable’ (as Ted Heath referred to Britain) maelstrom.

In 1979

Thatcherism launched its assault on society and the Keynesian state. But simultaneously it began a fundamental reconstruction of the socio-economic architecture with the first privatizations... Thatcherism thoroughly confused the left. Could it be not just another swing of the electoral pendulum but the start of a reconstruction of society along radically new, neoliberal lines? ...

[Thatcher] impelled people towards new, individualized, competitive solutions 'get on your bike', become self-employed or a share-holder, buy your council house, invest in the property owning democracy. She coined a homespun equivalent for the key neoliberal ideas behind the sea-change she was imposing on society; value for money, managing your own budget, fiscal restraint, the money supply and the virtues of competition. There was anger, protest, resistance - but also a surge of populist support for the ruthless exercise of strong leadership.

Hall is right to note the role of Thatcher as a strong leader in the eighties, which contributed hugely to her popularity. Unlike Heath, she did not appear to buckle under the pressure, did not resign Britain to being 'ungovernable'. At the end of eighties Thatcher and Thatcherism uncoupled, taking different trajectories. Thatcher was deposed by her own party in the wake of the poll tax riots, as they feared that she had pushed the people of Britain too far, and a decade of resentment had been building towards the party. John Major took over the party in 1990, and steered them back to the middle ground, reaching there before a Labour party which, under Neil Kinnock, had also moderated itself, largely by expelling the Trotksyist group Militant from its ranks. It was not until the re-branding of Labour under Tony Blair in the mid 1990s that they finally took back power.

This is where the political theory of Thatcherism returns - a Labour party willingly bereft of its social democracy, working class roots. As Hall notes:

But the 'middle ground', the pin-head on which all mainstream parties now compete to dance, became the privileged political destination. New Labour believed that the old route to government was permanently barred. It was converted, Damascus-like, to neoliberalism and the market.

Rather than attempt to reverse the destruction of industrial communities around the country, Labour simply forged on with the Thatcherite view that humans are inherently selfish. It catered overwhelmingly to the expanding middle class (which, in reality, was merely a brand of proletariat with a different quality of life and a collapsing class consciousness). Take, for example, the case of being able to buy your own council house. Remove the status symbol of a mortgage, and there is little difference between owning your own and continuing to rent. All you have done is contribute to the growth of a profit-driven market in housing, which, as a basic human need, should not be given over to the realm of private sector profit (as with health or education). New Labour persevered with this idea, as it believed that the free market could be used to lift people out of poverty - this runs parallel to the belief that working can lift you out of poverty, and is no less inaccurate.

One thing that Thatcher recognized about neoliberal economics, and capitalism in general, is that it must combine the opposed concepts of a free market with a strong state, in that the market must be protected so that it can flourish. Thatcher started the erosion of civil liberties in Britain, attempting to smash its enemies as much as possible. Her government used the police as a private army against striking miners, going out of their way to protect the police from any prosecution. It also eagerly took part in collusion with loyalist terrorist groups in Northern Ireland to murder civilians (when it wasn't just using the army to murder civilians, that is), and used a war over a tiny rock in the Atlantic Ocean to further the cause of British nationalism and imperialism into the twentieth century. This flexing of state muscles continued with Blair, who ignored the vast majority of people who opposed his illegal Middle East wars, and happily ignored the concept of human rights - be it against peaceful protesters, or terrorist suspects who were tortured. There was also nothing done to reverse laws which clamped down on trade union activity, giving Britain the staunched-policed workforce in Europe.

The Coalition government are happily advancing the free market/strong state idea (as they obviously would) but what is more worrying is the complicity of Ed Miliband and Ed Balls to conform to the neoliberal blueprint.

Miliband has spoken of his admiration of Thatcher before, but the willingness to lazily conform to this hegemony is no more apparent in the case of the recent 'strivers' vs. 'shirkers' development.

‘Strivers’ vs. ‘shirkers’

Classifying the people of Britain in two distinct camps was, in this case,

Cameron's idea (he used the word skivers, but the intent was the same). Strivers are people who work hard, shirkers are people who attempt to avoid it.

It is, of course, a lazy, and horribly reductive. It is, politically speaking, a good move, as it means you do not have to stretch yourself attempting to appeal to more than one group - just set out two camps, and wait for the people to come to you. It does not look at the role played by people who are out of work, and want to be in employment, but cannot because there are not enough jobs being created. Or people who are in work, but skive their way through it. People who cannot work. The idle rich.

It is a classic, simplistic case of divide and rule, motivated by a series of

lies and slanders aimed at the poorest people in society. And Labour have bought it.

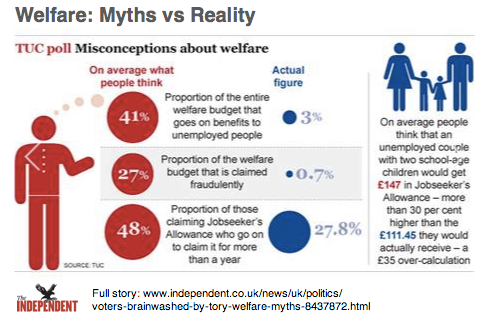

The Independent today has ran a

front page story highlighting the truth behind the stats which roll from the tongues of Tory ministers who want to shame anyone on benefits - at the same time the Labour party have

unveiled populist new plans to force anyone unemployed for over two years to take a job lasting six months, otherwise they lose their benefits. This again, is simplistic, ignoring the reality that there are not enough jobs being created, and playing into the idea that anyone unemployed for that length of time is simply 'idle'.

The complexities and failures of a jobs program by both main parties are for another blog post - what it serves as here is an example of the unwillingness of the Labour party to take the tough road (the 'old route' as Hall referred to it above) back to power. It has neglected its roots as a social democratic party for electoral reasons, which, at first, seem common sense. It was Thatcher herself that showed that hegemonies and established systems in Britain could be challenged, through her dismantling of the welfare state. Labour could channel the dissatisfaction with neoliberalism, and highlight its obvious failures. In this context, it would prove to be a greater opposition than it could ever be currently. There is a timidness in the way with which Labour approach politics these days - it no doubt fears electoral ineffectuality. On its current path, it is already ineffectual.